“Forgiveness does not change the past but it does enlarge the future” Paul Boese

Forgiveness means letting go of resentment and retaliation by recognizing that perpetuating the conflict only hurts us more. While an authentic apology can be effective in restoring interpersonal relations, forgiveness goes one step further; it enables healing and allows each person to move forward in their lives without guilt, bitterness or power games that can reignite the conflict.

Forgiveness does not mean that we condone another’s action, but that we choose a different response and regard the situation as an opportunity for growth. But how easy is it to forgive?

Our willingness to forgive depends on how one relates to the factors in play when considering it:

- Empathy for self and other

- One’s worldview/assumptions: how we see ourselves, others and life

- One’s sense of identity and self-esteem

- One’s vulnerability, truth and congruence

Empathy:

How we treat ourselves when we make a mistake can reflect on how forgiving we are of others. Do we tell ourselves that we are ‘a bad person’, or that we made an error of judgement? Are we more lenient on ourselves than we are on others, or vice versa? Or are we equally kind to both?

If we are hard on ourselves, we may lack empathy and understanding for the part of us who was in pain when it acted out. We may then wish to ‘punish’ another rather than explore the reasons behind their action, their situation and worldview, how they perceive us and our behaviour.

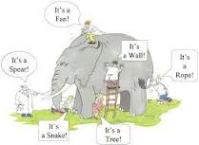

While empathy is inclusive, blame is exclusive. Empathy enables compassion for each other’s humanness and facilitates personal insight. It helps us move away from blame and opens reflection from the ‘And-principle’. For example: “This happened and it hurt me and they saw things from their perspective and I may have contributed and they were also in pain and we may both be hurting.” In other words we see the human in them and in ourselves. Empathy does not minimize the act; it simply helps us detach from it.

Our Worldview and Assumptions

While we may justly feel hurt by another’s action, holding on to hurt and anger harms us more. Simply put, we remain frozen in the past; we twist the knife into an unhealed wound and this calcifies our assumptions.

We may consequently convince ourselves that it is true that:

- Others cannot be trusted and that not forgiving helps us remain vigilant to it reoccurring

- It’s not ok to make mistakes and that these require punishment and repentance

- Life is a struggle for power, which we must win in order to survive

- To forgive is a sign of weakness

Not forgiving keeps us stuck in blame and power-games, which, however unconsciously, perpetuate the conflict in order to validate our hurt position and justify our actions. As a result, we can become so used to living with the ‘story’ that we don’t remember who we are without it.

Our sense of identity and self-esteem

By considering forgiveness however, we embark on an inner journey of healing and learning that exposes our vulnerability. Through it, we explore how we regard ourselves in relation to others and the extent to which this is driving our attachment to the event.

- Do we regard our self-esteem as equal, or unequal to others?

- Do we err towards grandiosity or inferiority, or regard ourselves as ‘ok’ despite our creases?

- Who, what and how would we be without the story?

If we regard our identity from an ‘all-or-nothing’ perspective and a sense of competition, then forgiveness feels like a sign of weakness and a loss of validity. “If I forgive, it means that it’s ok for them to walk all over me.” One consequently hangs onto the story to make a point and enforce one’s self-esteem.

Conversely, if we regard ourselves as equal to others, we are able to forgive without our identity being affected. From this place, our response may be: “This hurt me and I can forgive, knowing that it doesn’t mean that I’m above or below them.”

Our self-esteem also drives our ability to forgive ourselves; can we be empathic with ourselves, or do we seek external absolution and approval?

Vulnerability, Truth and Congruence

By allowing our vulnerability, we reconnect to our true selves and not the wounded ego running the show through the defensive ‘acts’ of tough guy, victim, drama queen, superiority and so on.

From this authentic place we can consider:

- The impact of our actions on another and on ourselves

- The congruence of our behaviour with who we truly are

In so doing, our true feelings emerge beyond the ‘acts’ and we can hear our own “And and And”. We gain insight into the wounds that inform our actions and can heal and release ourselves from these.

This does not mean that we blame ourselves for the situation, but that we unhook ourselves from the story. Ultimately, we cannot change another or the past, but we can change our response to them and the situation.

Conclusion:

Forgiveness is a choice between conflict and pain, or calm and moving forward. Choosing to forgive takes greater courage and strength than perpetuating the story, because we are embracing our vulnerability and valuing ourselves and our well-being Through it we are releasing ourselves from the toxicity that continued conflict brings: resentment, stress, ill-health . . . We free our mind to think about other things; to reconnect to ourselves, to our loved ones and our lives.

It is important that when we forgive we do not regard ourselves as superior, for this is not real forgiveness but a power game. Perhaps we may also need to forgive ourselves for choosing to forgive and reason with the part that sees it as a sign of weakness.

Forgiveness is possible whatever the crime. The Forgiveness Project narrates the journeys into forgiveness by victims of the most heinous crimes. The crime does not change, but one’s response to it can.