Our minds can race faster than a Ferrari Testa Rossa!

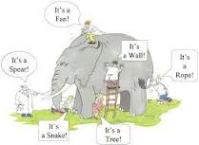

Our assumptions are triggers in conflict. How we see life, ourselves and others can create, escalate or de-escalate a situation. A thought can take hold and before we know it, it’s overtaken our thinking. Such thoughts are often based on suppositions we take as ‘fact’. They can make us miserable, cloud our reasoning and create an Amygdala Hijack.

This anecdote shows how we do it. 🙂

Jim decides to ask his friend John if he can borrow his TV for an hour.

He puts on his coat and walks to John’s house. With each step he takes, his doubts about John’s response grow. He tells himself: “You know what John’s like, he can be tight with his things – remember what he said to Sally last time? Yeah, well, I’ll tell him it’s just for an hour – I don’t want it forever! And anyway, when was the last time I asked him for anything? What’s the big deal, it’s just for an hour?!”

The more he convinces himself that John is going to be a pain about it, the more irritated Jim gets. By the time he reaches John’s house, his blood is boiling.

He knocks on the door.

John opens it and smiling warmly, says:

“Jim! What a lovely surprise! Come in!”

Jim doesn’t move; his jaw tightens. Glaring at John, he says:

“You and your TV, F%*k off!”

Whether we go as far as Jim or not, we still do the ‘You and your TV act’ more often than we may care to admit.

We may or may not be conscious of our assumptions; we may make them because we are too shy to ask for clarification or because we have little time at work and we need to get on with the job at hand. However we are feeling, making them gets us in trouble and, as the saying goes, “Assumptions make an ass out of you and me”!

There are two specific types of assumptions that influence our thinking and behaviour:

1/ ‘Factual’ Assumptions: the assumptions we make about information and actions, which we regard to be ‘facts’, but are really only our interpretation of them. For example:

“I’m not sure what s/he means by that, but I assume it’s . . .”

Or, interpretations and diagnoses of others’ intentions based on the impact their actions have on us:

“I bet X said it on purpose just to show me up!”

2/ Personal Assumptions: those we make about life, others and ourselves based on past wounds, from which we now operate and experience the world

For instance:

- “Life’s a struggle”

- “Others are unreliable /takers / lazy/mean”

- “I am not good enough”

- “I’m unlucky in love/ work/ life”

How they work:

These assumptions act like ‘magnets’ from which we unconsciously attract similar situations that prove us right and trigger our responses. They become self-fulfilling prophecies and are the origins of our self-sabotage. When we engage in them all alternative thoughts and actions disappear under the dark cloud of all-or-nothing thinking.

In Jim’s case, he assumes that John said ‘no’ to Sally because ‘he is tight with his things’. By assuming this, Jim eliminates the possibility that John’s refusal may have been circumstantial rather than simple selfishness on his part.

These two types are inter-related – we interpret ‘facts’ based on our personal assumptions.

For instance, Jim’s magnet may well be that “Life’s a struggle and others are mean”. John’s refusal to Sally becomes a ‘fact’ to Jim and confirms his personal assumption. He then bases his subsequent thinking on these combined conclusions and suffers an Amygdala Hijack in which his belief about life and people is reconfirmed – albeit in his mind.

This is what my sister calls ‘fighting the invisible man’!

When these two types of assumptions take hold we:

- Assume the worst about life and others and we enter into either/or thinking

- Accuse rather than clarify them with those involved

- Lay ourselves open to an Amygdala Hijack and reconfirm our negative worldview

In no time at all, the world looks bleak and we feel hard-done by.

Seeing conflict as an opportunity for growth, both personally and inter-personally, can help us move from assumptions and confrontation to clarification and cooperation.

We can interrupt this vicious cycle and de-escalate our thoughts by:

- Reality checking. We ask ourselves how far this is actually a fact and check it out with the other person

- We take a moment to ask ourselves what assumption/magnet we are operating from – doing so helps us regain our power from any situation, review our future actions and stop an Amygdala Hijack

- We consider alternatives to our thinking – how else can we see this situation? What if this isn’t the case?

Another very simple and effective reality-checking tool is to remember Jim and John and tell yourself “You and your TV!” This quick reminder makes a bleak situation more humorous and helps us reconsider the situation from another perspective. 🙂